Toward Truth & Reconciliation

By Sharon Sliwinski

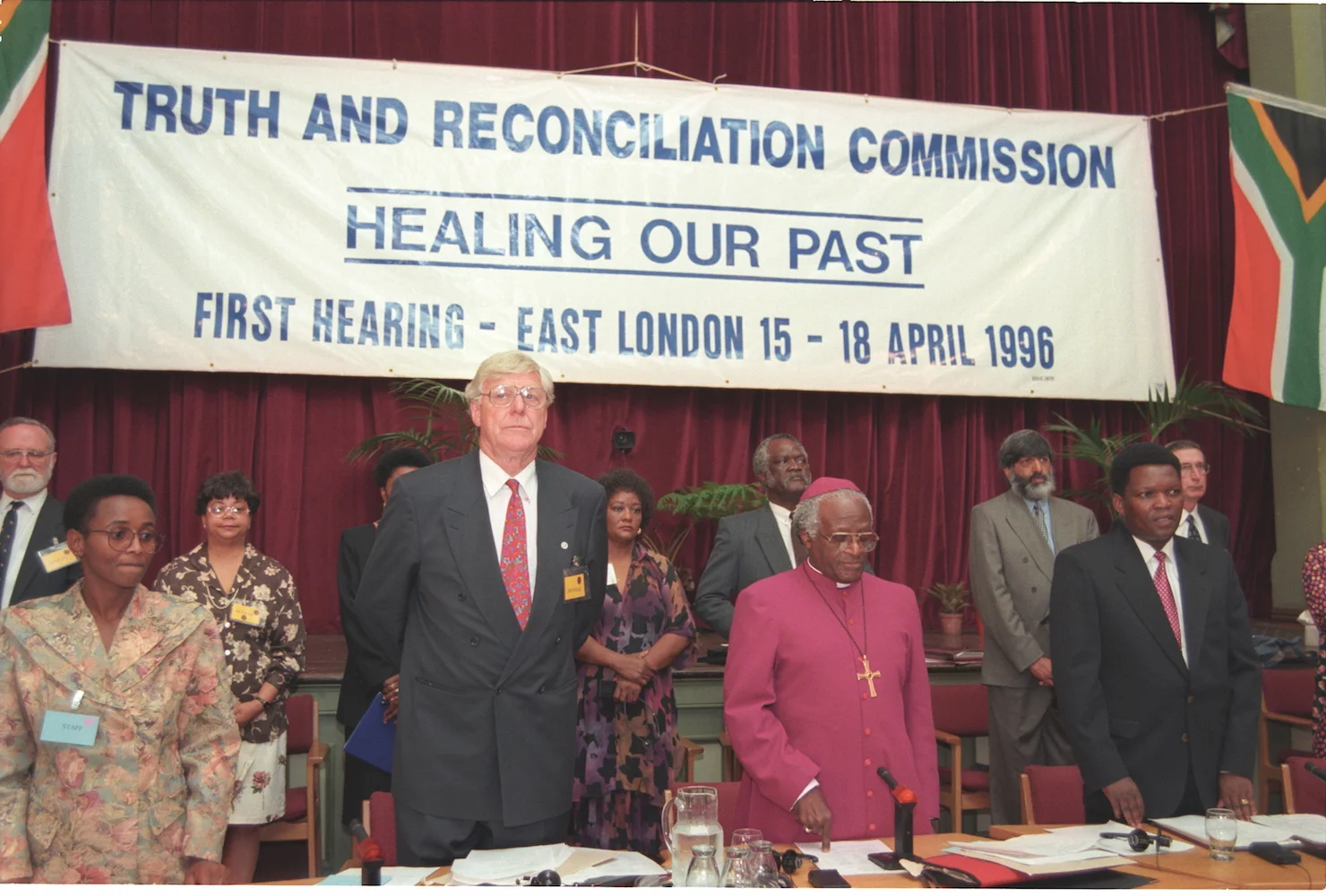

After apartheid was finally abolished in South Africa in 1994, the newly elected President Nelson Mandela established the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) so the country could begin to come to terms with its history. Headed by Archbishop Desmond Tutu, the mandate of the Commission was to record and bear witness to testimony relating to human rights violations, and to assist with rehabilitating and restoring victims' dignity. The process also involved considering amnesty applications from perpetrators of violence from all sides.

EAST LONDON, SOUTH AFRICA - 1996: Archbishop Desmond Tutu, Chairman of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission at the first TRC hearing in East London.(Photo by Oryx Media Archive/Gallo Images/Getty Images)

During the two years of hearings—which lasted from April 1996 to June 1998—some two thousand testimonies were delivered in public before the Commission. The commissioners went out of their way to provide a forum for marginalized voices from the rural areas. One of these voices was Ms. Notrose Nobomvu Konile, who's son Zabonke had been killed in 1986 in the infamous Gugulethu Seven incident (in which seven anti-apartheid activists were murdered by the South African police). In the course of her testimony, Ms. Konile described a bad dream about a goat that she experienced on the night before she heard of her son's death.

This particular testimony made an impression on Antjie Krog, who covered the TRC hearings for the South African Broadcasting Corporation—not because it was particularly affecting, but because it was the most illegible narrative that she had heard. The TRC was not a forum for dreams, but for the truth about human rights abuses, and neither the commissioners nor the media could make sense of Ms. Konile's strange attestation. Because Mrs Konile “failed” to narrate her story effectively to the commission, her testimony was dismissed as being incoherent.

Krog came to suspect that this illegibility was due, in part, to problems of translation: Ms. Konile had testified in Xhosa and the hearings were largely conducted in Afrikaans. But Krog also wondered if some vestiges of "cultural supremacy" had prevented this woman from being properly heard and understood.

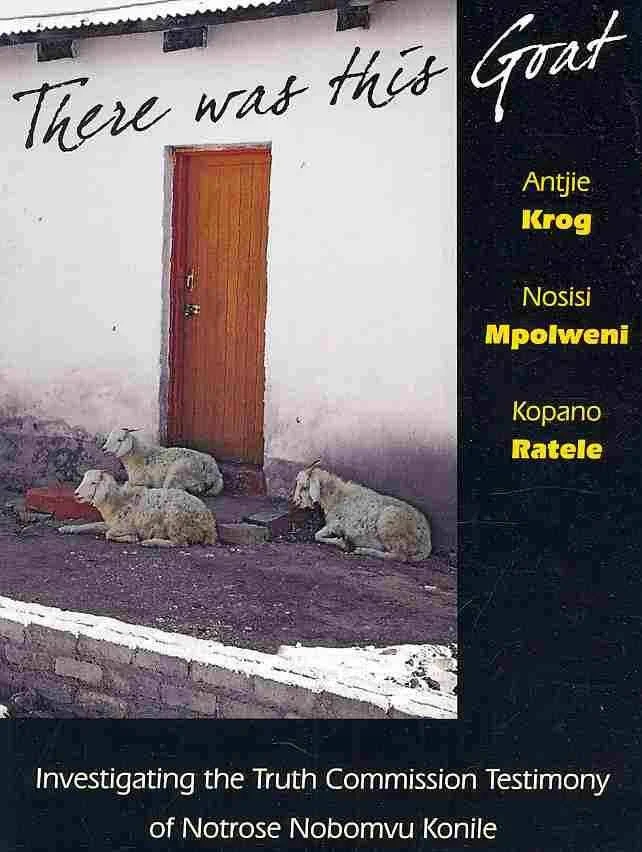

Together with two colleagues, Nosisi Mpolweni and Kopano Ratele, Krog embarked on a closer study of Ms. Konile's testimony. The three-year collaboration drew on different disciplinary and theoretical traditions to pose questions about the unacknowledged assumptions that underpin cross-cultural dialogue. Their co-authored book, There Was This Goat: Investigating the Truth and Reconciliation Testimony of Notrose Nobomvu Konile, uses Ms. Konile's testimony to explore complex questions about how South Africans might build bridges towards understanding one another across profound cultural, social, and economic divides.

Subsequently, one of Antije Krog’s students, Sandiswa L. Kobe, retranslated parts of Ms. Konile’s testimony, emphasizing the fact that the form of her storytelling followed the conventions of isiXhosa traditions:

The goat is not just an animal used for rituals in the isiXhosa religion and culture. To dream about a goat is a loaded statement; loaded with cultural connotations. In the isiXhosa, religious culture to dream about a goat standing near the door or inside the house is considered bad. It means either something has gone totally wrong or something is about to go wrong. Mrs Konile tried to suggest to the TRC that she did not find out about her son’s death from neighbours, employees or television. She knew something had gone wrong [because of her dream] and that it was related to her children. Mrs Konile was so alienated by the TRC processes that she was not able to speak to the processes and the processes were not able to get through to her.

What is lost when expressions of human suffering are pressed into the recognizable, standardized language of human rights claims? There Was This Goat teaches its readers that dreams can be important vehicles for marginalized people to enter dominant discourses and speak on their own terms and in their own cultural genres. These surprising disclosures can expose important questions about the ethics and politics of interpretation, and indeed, inspire new modes and models of cross-cultural engagement.

Collections page image: Diane Whitehead, "Goat Gloat," oil on canvas, courtesy of Diane Whitehead.