Between the work and the world

By Nataleah Hunter-Young

Sethembile Msezane, Chapungu—The Day Rhodes Fell, 2015. Courtesy of the Artist.

I never in my life thought I would see a police station burn; the thought now keeps me warm.

– El Jones in Hunter-Young & Riley-Case, “Thoughts of Liberation”

The second reflection concerns the difficulty of trying – as I have – to make connections between works of art and wider social histories without collapsing the former or displacing the latter. Despite the sophistication of our scholarly and critical apparatus, we are still not very far advanced – especially when the language concerned is the visual – in finding ways of thinking about the relationship between the work and the world. We make the connection too brutal and abrupt, destroying that necessary displacement in which the work of making art takes place; or we protect the work from what Edward Said calls its necessary ‘worldliness’: projecting it into either a pure political space where conviction – political will – is all, or an inviolate aesthetic space, where only critics, curators, dealers and connoisseurs are permitted to play.

The problem is similar to the relationship between the dream and its materials in waking life. We know there is a connection there. But we also know that the two ‘continents’ cannot be lined up and their correspondences read off directly against one another. Between the work and the world, as between psychic and social, the bar of the historical unconscious, as it were, has fallen. The effect of the unseen ‘work’ – that which takes place out of consciousness, in the relationship between creative practice and deep currents of change – is thereafter always a delicate matter of re-presentation and translation, with all the lapses, elisions, incompleteness of meaning and incommensurability of political goals these terms imply. What Freud called ‘the dream-work’ – in his lexicon, the tropes of displacement, substitution and condensation – is what enables the materials of the one to be ‘re-worked’ or translated into the forms of the other, and for the latter to be enabled to ‘say more’ or ‘go beyond’ the willed consciousness of the individual artist. For those who work in the displaced zone of ‘the cultural’, the world has somehow to become a text, an image, before it can be ‘read’.

– Stuart Hall, “Black Diaspora Arts in Britain”

By NATALEAH HUNTER-YOUNG

June 1, 2023

On April 9, 2015—while studying for her master’s degree at the University of Cape Town—the artist Sethembile Msezane was in a meeting with her advisors when one of them mentioned that the Cecil John Rhodes statue on campus would fall that day. One month prior, on March 9, Chumani Maxwele had infamously hurled human excrement at the bronze statue of the mythic imperial figure, thereby igniting a series of protests on campus that demanded that the university take immediate action to remove the monument.

The hashtag #RhodesMustFall quickly circulated on social media, driven by movement protestors whose decolonizing demands addressed and far exceeded the university’s built environment. Notably, students struck up long-fought battles such as those over the language of instruction and enrolment fees. The hashtag #FeesMustFall would soon attach itself to the movement discourse, advocating free education for all and spreading widely across universities nationally (Rhodes University and Stellenbosch University in 2015; University of Pretoria and University of the Free State in 2016) and their colonial sister-institutions abroad (University of Oxford).

These campus uprisings, between 2015 and 2016, spawned the fallings of imperial monuments globally into present day—slaver Edward Colston in Bristol, U.K.; Rhodes (again) at Oriel College at Oxford; Leopold II in Brussels, Belgium; invader John Fane Charles Hamilton in Aotearoa; slaver Robert Mulligan from in front of The Museum of London Docklands; cultural genociders Egerton Ryerson from Ryerson University in Toronto and Canadian Prime Minister John A. MacDonald from a downtown park in Kingston, Ontario; and conquistador Christopher Columbus (many times) across the U.S. These fallings paralleled long-fought actions against confederate monuments in the U.S., however visually, in the popular imaginary fostered through U.S. corporate social media, the twin struggles blended together.

I met virtually with Msezane in December 2021 to discuss her viral performance-photo “Chapungu — The Day Rhodes Fell” (2015), which took on an iconic and unexpected emblematic quality alongside the initial movement’s aims. In discussing that work, Mesezane shared with me a parallel narrative, namely that of the Chapungu eagle that travelled to her in recurring dreams and led to the making of the embodied work—part of a series of works titled Kwasuka Sukela. The artist also shared her reflections on the viral visual economy into which the performance-photo was thrust.

Hunter-Young: I do want to speak to the very explicit connection that people are making between the present and the past through these monuments and the monuments coming down as symbols of colonialism. Do you have thoughts and comments on how you’ve seen that [evolve over the last six years]?

Msezane: This is something that was always going to happen. What happened in 2015 was not the beginning. We stand on the backs of so many other students, ancestors who fundamentally said, “We exist and you’re trying to erase our existence, absorb our belief systems and alienate them. It is not going to stand forever. Our children will also speak.” I think the monuments in themselves, they’re sort of like spectral beings in that they have witnessed time change but they have remained stagnant. In them being there, we start not to see them but their spirit is still very much alive. And their legacies are still alive [so] to still choose to have [these colonial monuments] there, cements and makes it fundamentally permanent what colonialism was trying to do in our lives… to make sure that it is there forever so that there aren’t any more lessons that need to be taught by whipping a slave, that we start doing the whipping ourselves, you know? And that we see something as benign, as a statue, as if it’s nothing, but actually it’s so powerful.

Recorded in Kayum Ahmed’s archive of activist testimonies are the visual-material anti-aesthetic logics of disruption that were actioned under the banner of Fallism—something Maxwele’s catalyzing performance realized so distinctly. To disrupt the brutal aesthetics of compromised freedom—what Ahmed via student activist Simon Rakei interprets as “abnormalizing space through disruption”—a physical actioning was required.

The symbolic targets became the enshrined relics of empire delegitimized as masking an enduring colonial project in South African higher education. Ahmed argues for Fallism’s consideration as both “a collective noun to describe the student movements” and, importantly, “a decolonial option that emerges from the university’s margins to crack [its] epistemic architecture.” As Msezane describes, this anti-imperial eruption was (and is) an inevitable part of the colonial project. It is not going to stand forever.

In her TED Talk, Msezane explains: “You see, public spaces are hardly ever as neutral as they may seem… Cape Town is teeming with masculine architecture, monuments and statues… This overt presence of white colonial and Afrikaner nationalist men not only echoes a social, gender and racial divide, but it also continues to affect the way that women—and the way, particularly, black women—see themselves in relation to dominant male figures in public spaces. For this reason, among others, I don't believe that we need statues. The preservation of history and the act of remembering can be achieved in more memorable and effective ways.”

Sethembile Msezane, Untitled (Freedom Day), 2014. Courtesy of the Artist.

The artist talks about how these symbols wear onlookers down. Even though they may appear unremarkable, we are in constant engagement, receiving constant messaging about our social world and the place (or non-place) for Black life in relation to it.

Msezane: That [anti-imperial] consciousness, it’s like a wave, you know. It ascends and then it descends again. And it ripples as well. So I think this was bound to happen across the world because it’s just time… Our spirits are tired… People are having spiritual awakenings which I also believe is a part [of what is happening]. As much as statues and the monuments are concrete or bronze or whatever, they are… they carry spirits within them. As the youthful, people who are living now, we carry the spirits of our ancestors as well. They are troubled by these statues that are still there, but it’s not just about the statues, it’s about what they stand for.

And so naturally I believe that we were going to have an uprising against these, not just the statues, but basically what they stand for because it just has always been something that just has not been right. It hasn’t been. We can’t justify what colonialism has done to everyone, Black, white, all kinds of races. Everyone has been affected and it just takes I think a few people around the world who are more spiritually aware to be part of a movement of driving about change.

I think when people think about such topics, they think about it from a very political sense as if there is no other way of being. But I think spirituality can also be quite political. Because this is spiritual warfare. They came into Africa and they took away our names. Hello! They know that we have naming ceremonies, doing things like that, there was an intention. Take away their names, take away their culture, take away everything and they will not know who they are. That’s spiritual warfare.

Hunter-Young: Yes, spiritual warfare. I think that’s a really useful framing. [The language used in the awakening here with regard to how Canada has treated the Indigenous people of these lands] has been “cultural genocide,” but I think spiritual warfare captures something that is more active, something that hasn’t stopped. Genocide [has a sense of finality—which is also why people speak of ongoing genocide]. But spiritual warfare does a lot more to capture the ongoing. I mean, as I’m reading—and Rhodes died more than a hundred years ago which still actually isn’t that long ago—the permanence Rhodes has as a cultural figure [still today] far outweighs [what one might expect considering the sociopolitical strides Southern African state officials profess to have achieved]. He’s too monumentalized for the atrocities that we know have been done in his name, by him, continue to follow from him. So I really like that framing of “spiritual warfare.”

Msezane: Whether we like it or not our spirits are working overtime. Our minds are working overtime. You get home and you’re tired and you want to take off the armour and you’re not sure why you’re so tired because you did something that you do every day. You went to work, you went through the city maybe to get home and that’s it. You didn’t do any more but you are so tired, why? Because all of the things that are around us are communicating something to us and that takes a lot of our sensibility to block out.

What Msezane shares about blocking out signs is true as well for refusing to block them out—for staying attuned to them even if only for some of the time. Spiritual warfare invokes the metaphysical onslaught without abandoning the material condition.

Early in our discussion, I make the presumption of referring to Msezane as a “performance artist,” to which she gently corrects me: “I identify as a visual artist because I trained within the visual arts—photography actually but I found my voice through performance.” She has learned through her practice that the ideas that come to her she does not come up with entirely by herself. “The visual stuff is in my mind or it starts in a dream but it’s always a visual before I can action it into something else. And because I work in different disciplines the visual umbrella is just much better than locking myself within performance because depending on what it is that I need to communicate, I will use a specific discipline.”

Msezane explains that when she began having recurring dreams of a bird when heading into her graduate studies, she felt compelled to “bring her into being” and “imagine what she would be like” through the material fashioning of wings. Made using synthetic hair, it was her then-unfinished wings that immediately came to mind when her advisor mentioned the University was planning to fall the Rhodes statue that day. Practicing in the space of the visual rather than “locking” herself into performance allowed an element of material autonomy to the vision that had presented itself to her. Through Msezane, the vision will decide its own form: “It could be sculpture, it could be photography, it could be film, it could be anything. It just depends on what the visual is and how it also wants to translate itself because I’ve made works sometimes where it might be easier to, I don’t know, make a drawing or a photograph but actually what needs to happen, the dream that I had would [dictate] that it should be a film.”

Spirituality is central to Msezane’s practice, as is the matter of dreams and dreaming as an intermediary. Following her lead, I reference both here as (more-than-)visual knowledge systems within which anti-imperial aesthetic logics are cultivated. Msezane shared, “I’ve gone through a whole journey where I’ve had to understand that this was a gift that was given to me, it was not called ‘art,’ it was called ‘umsebenzi wezandla’ which is ‘gift of the hands,’ and what people like myself would do in their communities is that they would give it and share it with their community. Whether through a bartering system or as a gift—it is something that was supposed to be shared.”

The artist tells me that she grew better connected to her dreams by sharing them with her grandfather. Together they managed to unlock access to another world, ungovernable by colonial logics and within which she could engage as she wishes.

Hunter-Young: What has your reaction been to the circulation of Chapungu-The Day Rhodes Fell? That photo in particular, has just kind of exploded around the world in circulation, it’s quite memorable.

Msezane: I honestly did not expect it at all. I didn’t expect the kind of reception that it’s received over the years and even when it first happened, like I said, I didn’t know what I was doing because I hadn’t planned it. So to see how much media attention it had received really blew my mind. And I think it made me a little scared because it made me realize that there was a dimension to my work that I was not aware of yet.

There’s a virtual nature to my work—and not just to my work, but in essence to who I am as a person. I’ve always been a dreamer. I’ve always been a person who kind of processes my understanding of the world through the dreams that I have and this was the relationship that I had with my grandfather. I would dream something, tell him about it, and if he thought it had some sort of spiritual significance then he would go and consult a traditional healer. I guess I didn’t tell him about this one and then it turned out to be big. I guess I was a little concerned what all of this means because it was a part of myself that I think I was not awake to yet.

There was something in me that was brewing that I couldn’t quite explain and over time things have become a bit clearer. I know that there is power in the things that I dream now. I still process the world through dreaming. And I’ve got a deeper connection with my ancestors now and [I am learning] how respectful I can be in speaking up about some of these messages without revealing the sacred nature of them in my work. So I am in constant conversation with the spiritual world, with my ancestors and it can be hard sometimes to process that world because the one I live in is secular… It’s a battle of trying to find the balance between two worlds I am constantly trying to navigate and sometimes I’m not good at it, sometimes I am.

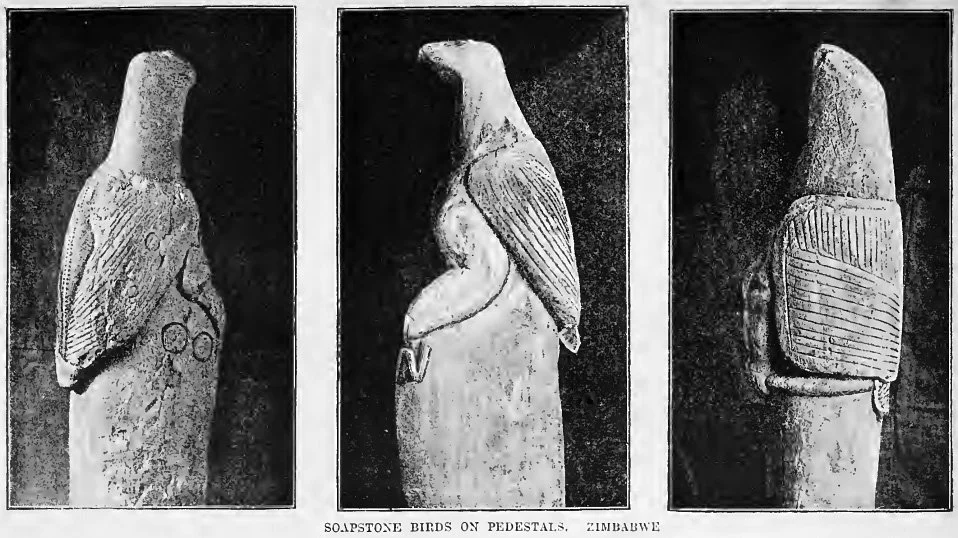

Illustration of the soapstone bird carvings at Great Zimbabwe. J. Theodore Bent, The ruined cities of Mashonaland; being a record of excavation and exploration in 1891. Longmans Green and co., 1895, pp. 181. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Chapungu and Great Zimbabwe

Rather than being the very form of the landscape, the Shona spirit world shadows or parallels the human world, and exists separately to it, with spirits acting as owners and guardians of the land and the people on it. At times, however, Shona spirits (the ancestors, Mwari and others) do manifest themselves in the landscape as rocks, caves, pools and trees. They can also appear as animals, especially lions and eagles, and perhaps most frequently of all, emerge among people themselves by possessing spirit mediums or appearing in dreams. In this way, parts of the landscape, certain animals and certain people can act as vehicles for communication between the parallel worlds of the spirits and people, particularly on ritual and ’sacred’ occasions when these separate worlds share time and space.

—Joost Fontein “Silence, Destruction and Closure at Great Zimbabwe: Local Narratives of Desecration and Alienation”

From the dreams Msezane was having heading into graduate studies, she would come to recognize Chapungu—the bateleur eagle considered a good omen by the Shona people of Zimbabwe, a symbol believed to bring “protection and good fortune to a community” according to Bongani Mkhonza. Eight distinct soapstone sculptures of Chapungu stood atop Great Zimbabwe, the 12th-to-16th-century stone metropolis located in the south-eastern hills of the country now named for it. Ruled by Shona Kings, Great Zimbabwe boasted mortarless towering architecture and is, by all accounts, observed as a place of great spiritual significance into present day.

Amplifying enduring narratives from local residents of the lands, following the medieval city’s 19th-century raid by European colonists, Joost Fontein explains that in particular, observers have recounted the absence of its “Voice, or voices and sounds that could be heard early in the morning, or in the evening.” According to Fontein, “beyond the material destruction of the site, or removal of objects, the process by which the site was turned into a [UNESCO World] heritage site is perceived above all else to have caused the anger of the spirits.” The induction of Great Zimbabwe into the leagues of World Heritage commemoration brought the addition of high fences, admission fees, and intense regulation of site access and use, leading to charges of “treating the site like a business (like their Rhodesian predecessors) rather than, as many had expected/hoped at independence, as a sacred site belonging to the ancestors.”

However, in a manner similar to Msezane’s embodied practice in previous works such as her Public Holiday Series, Great Zimbabwe is acknowledged for its living quality, where, as Fontein puts it, “[m]any people suggested that the sounds, voices and other ‘miraculous features’ could return if the place were again treated as sacred, if the ‘traditional’ rules and customs were followed, ceremonies permitted, and the ancestors and Mwari were again respected.”

The first colonial interference with Great Zimbabwe, initiating its structural ruin and spiritual violation, is attributed to German explorer Karl Mauch in 1871. Largely abandoned by the 1700s, according to Webber Ndoro, “Great Zimbabwe was probably used only irregularly for religious ceremonies—as it is today—until the late 1800s [when] Europeans arrived, lured by visions of gold from King Solomon’s mines, and it was then that the archaeological record became so damaged as to become largely indecipherable.” Ndoro continues, recounting the encounter this way:

German explorer, Karl Mauch, was first to arrive, in 1871. He befriended another German, Adam Render, who was living in the tribe of Chief Pika, a Karanga leader, and who led him to Great Zimbabwe. (Had he known the outcome, Render, who was married to two tribeswomen and well integrated, might have steered Mauch into the Zambezi River.) On seeing the ruins, Mauch concluded very quickly that Great Zimbabwe, whether or not it was Ophir, was most certainly not the handiwork of Africans. The stonework was too sophisticated, the culture too advanced. It looked to Mauch to be the result of Phoenician or Israelite settlers. A sample of wood from a lintel bolstered Mauch's rapid assessment: it smelled like his pencil; therefore, it was cedar and must have come from Lebanon.

I am assessing Mauch’s refusal of Great Zimbabwe’s ‘Africanness’ as an (imperially visual) aesthetic judgement to which immediately European regimes of knowledge sought to make meaning of, and assign value to, what his eyes and imagination were incapable of computing if he were to maintain his own self-regard. This European humanist self-regard, Sylvia Wynter teaches us is self-sustaining, or autopoetic. The abject becomes identifiable through aesthetic logics that instruct and affirm our relations to the world.

European plunderer Willi Posselt enters historical record shortly after Mauch, where he cut and looted at least one bird, hiding several others. It is this first looted bird that historians trace to the current possession of the Cecil John Rhodes estate at Groote Shuur in Cape Town. In 1889, Posselt sold the pilfered artefact to Rhodes, then-prime minister of the Cape Colony, who would endeavour to make it his “personal totem” (Ebrahim), something that Msezane tells me would eventually see iconic reference throughout the estate home—the doorknob, on top of the house, on the side of the stairwell. Msezane tells me to Google the Rhodes Scholarship, and I notice Chapungu is in its logo.

The logo for the Rhodes Foundation Scholarship and registered trademark of the Rhodes Trust. The graphic depicts an image of Chapungu, the Zimbabwe bird, figured inside a capital letter ‘R’. This research/researcher is in no way affiliated with the Rhodes Trust.

Hunter-Young: I was prepping for this, thinking about your Chapungu performance, or work, and then reading—thanks to the links on the TED Talk—about the great Zimbabwe birds being stolen. Even how it is described—“cut from its plinth.” That, when I read that and then thought again about “Chapungu-The Day Rhodes Fell,” you—Chapungu—have returned to cut Rhodes from this space. The echo is quite intense. What do you think about when you think about that work? Where does it live in your memory now?

Msezane: I know it is something that I could never in a million years have thought up because it literally happened in a moment in time and I couldn’t have been ready for that moment no matter how much one can plan for it. And as much as I make other work, I do think about that work and I say: “Wow, I wonder if I can try and recreate a similar moment?” And no, it’s impossible. It came at that moment because the message needed to be heard in that moment. I was not in the space quite honestly to be making such deeply profound work at the time. I was a student myself, I had just begun my master’s.

The issues that the students were tabling were the issues that I was experiencing in real time and I quite honestly did not have the energy or the mental capacity to be participating in a movement. I went to a few meetings but it was never my intention to be a part of a movement. I literally did not have anywhere to stay of my own. I was staying at a friend’s place and even then how we became friends is just so coincidental. I didn’t know her that well for me to be staying, crashing on her couch but that really, it eroded my self-esteem because I like to think of myself as a self-sufficient person but in that moment, Cape Town was doing to me what it has done to many Black people. Cape Town was refusing a person like me to have a home within the city. I had such trouble, even though I could afford to find a place to stay, I was just being discriminated against I believe because of my race.

So my master’s comes, and I don’t have the energy to look up what I’m trying to do for my master’s [project], and I’m having dreams about this bird [but I didn’t know what they meant because] at that time I wasn’t awake yet. But because I kept on dreaming about her consistently, I brought her into being through making. I thought of making wings and imagining what she’d be like. Also, I think I started to piece things together when I realized that I’ve been speaking about these statues for two years prior to the protests happening.

Clearly I‘m not mad—there is something to this. I think that’s when I was slightly twitching in my sleep. I wasn’t awake yet but I was twitching in my sleep. And then the day came when the statue would be removed and I didn’t even know that that was the day. I got told in a meeting by my supervisors and I was very confused… in my head somewhere I [thought] “the wings are not done.” I didn’t know why I was freaking out about these wings that I’d not done. “The statue is coming down today, what does it have to do with the wings?”

But in that moment I think I started to wake up, a very rude awakening. I realized what I had been preparing for. That the spirit of this bird was making me get ready for this moment, that as the statue falls that it is going to be in place rising. And to this day, I still have chills about that moment.

Hunter-Young: I have chills listening to you.

Msezane: I also wonder sometimes why the bird chose me to deliver this message, and in such a way. This is even before I really understood the connection between Rhodes (the figure) and Chapungu.

Hunter-Young: Wow.

Msezane: I didn’t even know who Rhodes was at the time. Then I searched Google (‘Rhodes the figure and a bird’) and I found out there is some sort of connection. But I shelved it away. It didn’t have the meaning that it has now for me. And over time, I think I [have come to] feel a bit helpless about that moment because for people it’s about the #RhodesMustFall movement, but for me the story was really about this bird that has been held captive since the late 1800s.

There is a reason why she came in that movement to reveal herself to people and it’s because she’s still not in Zimbabwe which is her home. She needs to be returned and I feel helpless because I can only do so much. I’m an artist, I’m not an advocate, I’m not a lawyer, I’m not a policy maker, I’m not a minister, so my power is very limited.

I’ve tried in having talks [on] various platforms, trying to re-initiate this conversation about repatriating the bird but I have no idea where the blockage is, what conversations are being had because there’s been conversations between governments in Zimbabwe and South Africa about returning the bird with various presidents. The late Robert Mugabe and Thabo Mbeki had the conversation, Julius Malema had the conversation, so I’m really not sure why it is.

Historian Henrika Kuklick’s book, Contested Monuments: The Politics of Archeology in Southern Africa, offers insights on the deep symbolism Chapungu held for Rhodes, who, in addition to gifting castings to friends, would have sculptures made three times the size to stand outside his British home in Cambridge. One report suggests Rhodes interpreted the soapstone bird as evidence of the abundance and prosperity north of the Limpopo river and south of the Zambezi, in Mashonaland (IOL)—where he would eventually send approximately 200 pioneering settlers in 1890 under the pursuant guise of gold mining.

With his “Pioneer Column,” Rhodes would send 500 British South Africa Company Police, who would ensure his capacity for the eventual annexation of the land, to become known as Southern Rhodesia. At this point, the European settler narrative is rewritten again under familiar aesthetic terms, as their “natural habitat.” Alongside attempts to cement among popular imagination that Great Zimbabwe could not possibly be the work of Africans, Kuklick identifies that a fundamental point of argument—between the British settler government and African freedom fighters—was the matter of when Great Zimbabwe was built, with settlers arguing for a placement in “ancient times” and revolutionaries, claiming “the relatively recent past.” Again, these are aesthetic distinctions with great visual-material bearing.

In “From Cecil Rhodes to Emmett Till: Postcolonial Dilemmas in Visual Representation,” Afonso Dias Ramos’ offers generative reflections on recent questions about monuments and imperial visuality, establishing that Rhodes was not highly regarded in life nor in the several years immediately following his death. Efforts to rehabilitate Rhodes’ image did not begin in earnest until the African national independence movements of the 1950s when, for example, South Africa’s National Party would seek to embrace “British Heritage and the Rhodes myth with fresh urgency.” This Rhodes myth is a vision of white majority rule, yes, but moreover it is an imperial visuality; coincidentally, one also made of dreams.

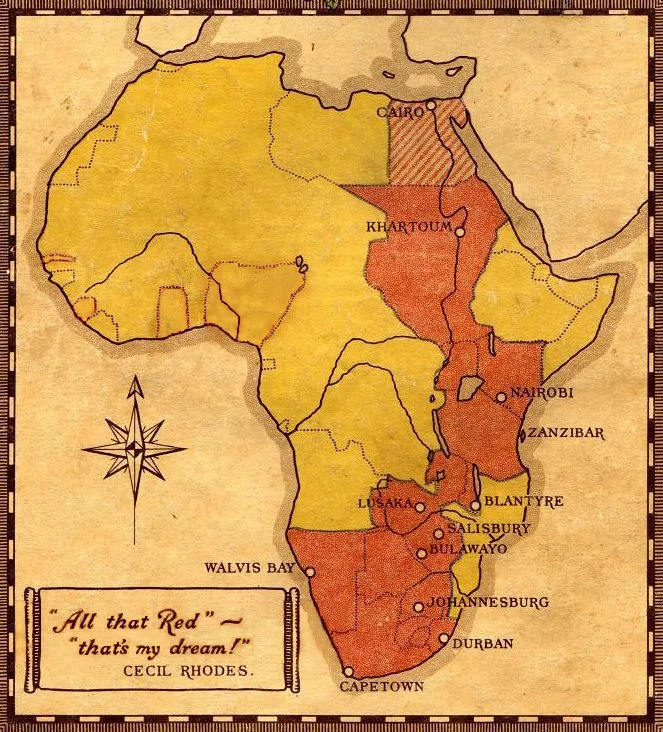

One of Rhodes’ greatest dreams was a ribbon of red, demarcating British territory, which would cross the whole of Africa, from South Africa to Egypt. Part of this vision was his desire to construct a Cape to Cairo railway, one of his most famous projects. It was this expansive vision of British Imperial control, and the great lengths that Rhodes went to in order to fulfil this vision, which led many of his contemporaries and his biographers to mark him as a great visionary and leader.

From the entry on Cecil John Rhodes in South African History Online

Artist Unknown. An image illustrating Rhodes’ dream of British imperial conquest in Africa. “British Possession in Africa, from Cape to Cairo” from the back cover of the British South Africa Company Historical Catalogue & Souvenir of Rhodesia, Empire Exhibition, Johannesburg, 1936-37. Reproduction of the catalogue available here.

With each attempt to mount the imperial visions Rhodes espoused via posthumous monument to his legacy, Ramos identifies Indigenous countervisualities that would refuse and remove him—a relational certainty of resistance that persists today. Then, tying the proliferating reproduction of Rhodes’s imperial presence in contemporary space and time to similar happenings on the other side of the Atlantic, Ramos importantly deduces:

In this sense, one can read the lynching of Blacks [sic] as a necessary counterpart to the monument of white domination. Images and statues should then be analyzed together as deeply interrelated phenomena… During the Jim Crow laws and the civil rights protests, confederate monuments such as Rhodes’s statues were placed strategically to inspire fear into the black population. As Till’s killers later admitted, they had lynched the schoolboy to send a message to the black community. Therefore, it was no accident that the peak of such monuments coincided with that of public lynching. Both enforced the same ends by different means: white superiority and black subordination. The photographic medium was deeply implicated in these operations. It amplified the warning as an image-transmission device. It ensured that the message was replicated, transmitted, and broadened for viewers beyond local communities. Violent images and sanitized monuments always exist in a dialectical tension, and the contemporary controversies are at pains to resolve this conundrum.

What “Chapungu-The Day Rhodes Fell” does is collapse the space between the work and the world, portraying an inevitable vision of Rhodes’ fall from undue grace. As Bongani Mkhonza writes, “this background theatre in Msezane’s artwork seems to seal the fate of Rhodes, as if ‘he’ was going to be destroyed either way.” Rhodes must fall.

“between the work and the world”

In “Black Diaspora Artists in Britain: Three ‘Moments’ in Post-war History,” Stuart Hall illuminates the space between the work and the world in which a genealogy of Black artists visually processed the task of anti-imperial image-world-making and identity formation through recollection and redesign. Fallism offers another contemporary “moment” or “conjuncture,” to think again with Hall, that is prime for close study.

What Fallism does for this generation, attuned to the newly networked digital visual field across which anti-Black state violence re-seeds globalizing ideas of nation, is reinscribe the globalizing task of anti-imperialism. Fallism offers a visual and material instruction on the still-present—though often made unseeable—colonial and imperial relationships that govern social life at the local and levels.

The imperial image-work of antiblackness is total climate. The air we cannot breathe. Artists can offer epistemic gateways to reconsider, to undo, the totalizing ambitions of colonial culture.

Hunter-Young: Is there a lesson that Chapungu gave you beyond what you’ve shared? (I mean, you’ve already shared so much).

Msezane: I guess her trusting her story with me showed me that I should trust myself more than I do. I tend to be in my mind a lot because, a lot is happening in the world but the added dimension of the spiritual realm is also something that I have to now grapple with. And I’m not as trusting of myself, my thought processes, my abilities but it’s weird because it’s also in my name. My name means “trust” and “hope” at the same time, depending on how you use it. And having such a sentient being trust itself with its legacy, with its history, a history that’s not even connected to my cultural purposes as a Zulu person—[or] maybe [it is since] borders are really just non-existent… Yah, I think I was very humbled by that.

The lesson really is that I do need to trust myself more and more. She’s also taught me that there is value within our knowledge system and that’s why it needs to be kept alive. That’s why more work needs to be made, more books need to come out of our cultures, we need to excavate all of these cultures and knowledge systems that were buried because they were buried because we were never meant to exist. But we are proof that we are here to exist. And we need to do something about fully embracing these knowledge systems otherwise they will disappear as imperialism had intended. These are the lessons that she’s taught me [and] I’m just like “OK, it started with you. Thank you. Now we go forth.”

Hunter-Young: It is really something to hear your journey to that moment in time and then to track what that moment in time has then done, visually. The messaging that has multiplied infinitely from something that came to you in a dream. It’s quite remarkable.

Msezane: I mean that’s a knowledge system in itself. The dream space has so much to offer. It’s a whole world, [it] communicates, it’s alive and we tend to cast it aside.

Nataleah-Hunter Young (she/they) is a writer, film curator, and Assistant Professor at the University of Toronto, Scarborough. Her research interests span the areas of Black Studies and Media Studies, focusing particularly on Black cultural production, political economy, research-creation, integrated arts and creative practice. Her writing has appeared in the Journal of Visual Culture, Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media, Public: Art | Culture | Ideas, The Conversation, Xtra, and Canadian Art, among other publications. At the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF), she is international programmer responsible for feature selections from Africa and Arab West Asia. Professor Hunter-Young holds a joint PhD in Communication and Culture from York University and Toronto Metropolitan University (formerly Ryerson).

Sethembile Msezane b. 1991 in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa. She lives and works in Cape Town, South Africa. Using interdisciplinary practice encompassing performance, photography, film, sculpture and drawing, Msezane creates commanding works heavy with spiritual and political symbolism. The artist explores issues around spirituality, commemoration and African knowledge systems. She processes her dreams as a medium through a lens of the plurality of existence across space and time, asking questions about the remembrance of ancestry. Part of her work has examined the processes of mythmaking which are used to construct history, calling attention to the absence of the black female body in both the narratives and physical spaces of historical commemoration. Msezane completed participated in the 13th Bamako Encounters African Biennale of Photography (2022) as well as the 14th Dak’art Biennale (2022), she was a UEA Global Talent Fellow hosted by the Sainsbury Research Unit and Sainsbury Centre (2021).

HOW TO CITE THIS ARTICLE: Nataleah Hunter-Young, “Between the work and the world,” The Museum of Dreams, https://www.museumofdreams.org/between-the-work-and-the-world/, June 1, 2023. Accessed [insert date].