We tend to forget the echoes of colonial struggles that found their way into The Interpretation of Dreams, above all because we rarely associate the Austrian context of the turn of the century with overseas imperialism. By a curious historical coincidence, Sigmund Freud’s discovery of the meaning of dreams, one of the most influential findings of the twentieth century, took place at the same time when Puerto Rico was passing to U.S. control.

In the name of liberty, justice, and humanity, American forces took control of Puerto Rico, beginning a new chapter in the Caribbean island’s colonial history. Upon occupation of the island on July 25, 1898, Major General Nelson A. Miles, as commander in chief issued a historical proclamation:

We have not come to make war upon the people of a country that for centuries has been oppressed, but, on the contrary, to bring you protection, not only to yourselves but to your property, to promote your prosperity, and to bestow upon you the immunities and blessings of the liberal institutions of our government. It is not our purpose to interfere with any existing laws and customs that are wholesome and beneficial to your people as long as they conform to the rules of military administration, of order and justice. This is not a war of devastation, but one to give to all the control of its military and naval forces the advantages of enlightened civilization.

In his invasion speech, MG Miles announced the advantages and benefits of “enlightened civilization” while expressing his desire “to put the conscience of the American people into the island.”

If the conscience of the American people was going to be put into the island, one may wonder, however, about the fate of the Freudian repressed, and most importantly, of the unconscious, now under the control of military and naval forces. To start answering, let me quote Freud; here is his dream, reported in chapter VI, of The Interpretation of Dreams.

A castle by the sea; later it was no longer immediately on the sea, but on a narrow canal leading to the sea. The governor was a Herr P. I am standing with him in a big three-windowed salon, in front of which rise projections of walls like fortress battlements. I belong to the garrison, perhaps as a volunteer naval officer. We fear the arrival of enemy warships, because we are in a state of war. Herr P. has the intention of going away; he is giving me instructions what to do in case of what we fear. His sick wife is with his children in the besieged castle. When the bombardment begins, the big hall is to be vacated. He breathes heavily and tries to get away; I hold him back and ask him in what manner I should let news reach him in case of need. Then he says something else, but at once his head sinks down dead. I may have overstrained him unnecessarily with questions. After his death, which makes no further impression on me, I wonder whether the widow should remain in the castle, whether I ought to announce the death to the Higher Command, and whether I should take over the control of the castle as next in command. Now I stand at the window and inspect the ships, which are passing by; they are merchant vessels, which rush rapidly past on the dark water, some with several stacks, others with bulging decks. Then my brother is standing beside me, and we both look out the window upon the canal. At one ship we are frightened and cry: “There comes the warship”. But it turns out that only the same ships are coming back which we have already seen. Now comes a little ship, comically cut off so that it ends in the middle at its broadest; on a deck there are peculiar cup or box-like things. We cry out in one voice: “That is the breakfast ship.”

In his analysis of this dream, Freud acknowledges that the dream contains allusions to the maritime war between America and Spain and to anxieties it had created about the fate of his relatives who have recently moved to New York. Freud explains that the deceased Herr P. appears as a substitute for himself, from which we may infer that he was one of the first casualties of the Spanish-American war. Freud's personal connection with the Spanish-American war could be seen as having wider implications. Perhaps the creator of psychoanalysis was already aware of the ominous consequences of American colonialist aspirations at a time when the United States looked to the Caribbean islands as a territory to conquer. What is even more ominous is that the dream describes an Etruscan urn looking like a boat, quite similar to the Greek urn in which Freud’s ashes were to be deposited in 1939.

In order to understand better the political implications of the day-residues that have elicited this dream, it is indispensable to recapitulate certain events that Freud does not develop in his analysis of the dream but that quite strikingly reappear in his recollection of the dream. They arouse our suspicion since they emerge in Freud’s dream not just as distorted remnants but almost word-for-word transcriptions of what he had read in Austrian newspapers about the Spanish-American war. Although Freud’s interpretation of the dream alludes to them in passing, since he seems more interested by idiosyncratic or private associations leading to a distant past (an enjoyable Easter trip to the Adriatic; a trip to Venice, some Etruscan pottery; mourning customs; funeral boats; gloomy thoughts of an unknown future), the material of the dream is brought by the curious historical events that took place in the month preceding it. In order to enhance scientific neutrality of his narrative, Freud chooses to downplay the obvious political content of the dream.

After a careful examination of all the issues of the daily paper, Leslie Adams asserts that this dream must have taken place on the night of May 10-11, 1898. This thesis is confirmed by all the curious details that crop up in the dream. At this time there were fears that New York might be attacked by the Spanish fleet. Freud’s dream recombines elements of the battle of Manila which was fought on May 1st and whose news reached the media by cable only a week after, on May 7. It is clear that Freud had read the relatively bewildering account of the battle which was spread over the first three pages of the Neue Freie Presse on the morning of May 10, 1898.

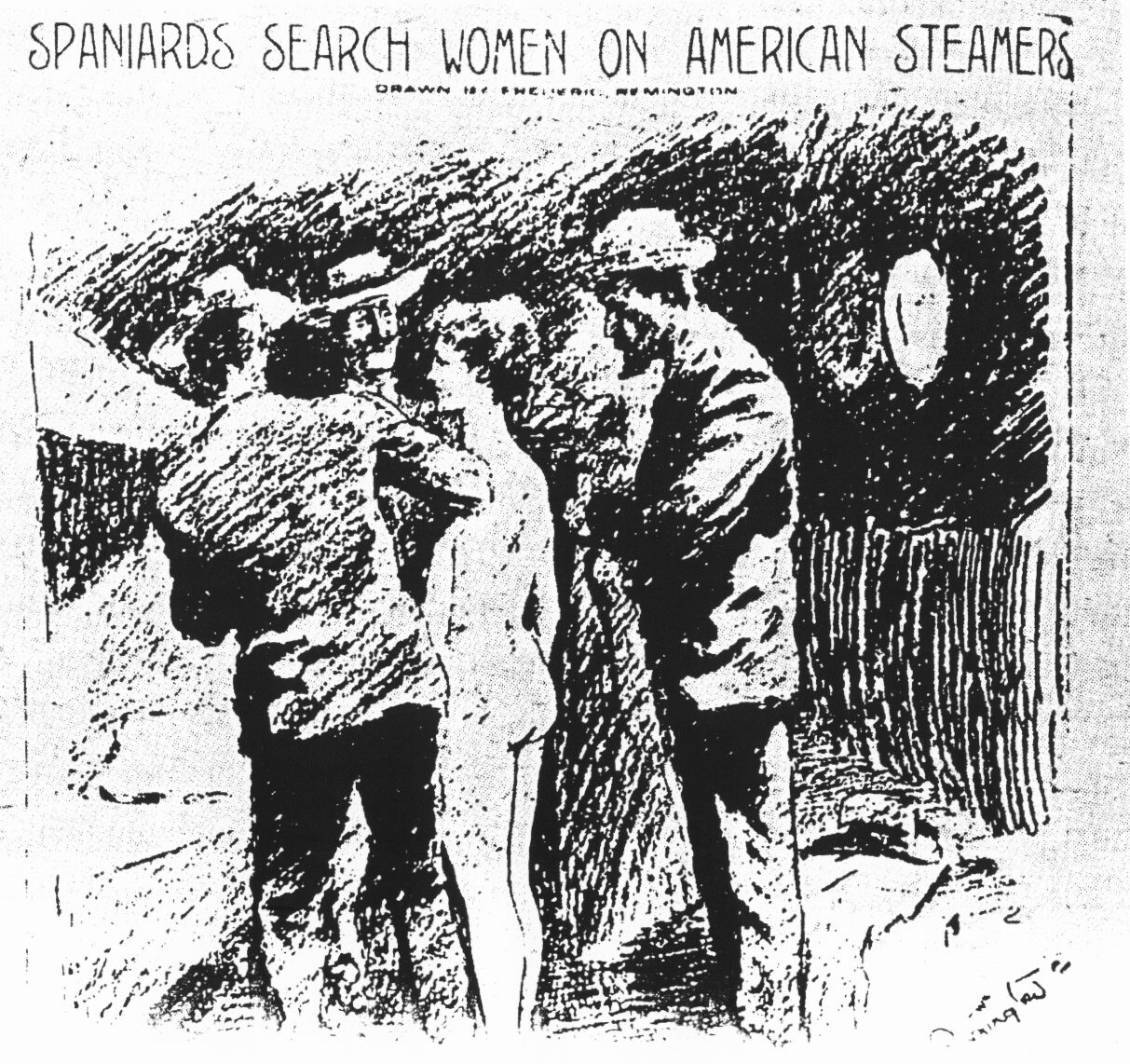

Hearst's "yellow journalism": Spanish officials strip search an American woman tourist in Cuba looking for messages from rebels (artist: Frederic Remington)

Here are the events that preceded the dream: after mounting tension between the Americans and the Spaniards, the USS Maine, which had come to the harbor of La Havana on a friendly visit, was shattered by an explosion and sank on February 15, 1898. President Mc Kinley was notified on his bedchamber that 266 Americans had been killed. The Hearst press began throwing the people into fury with a saga involving an endangered, virginal, young, beautiful woman who was kept unjustly in prison by the Spaniards. The actual war declared two months later, on April 22. By May 2, the world press reported that a strong Spanish squadron under Admiral Cervera had left the Azores and taken to the high seas in a westward direction. Would it attack America or the West Indies? The fear extended across the coast reaching as far as New York. Lighthouses were dimmed and buoys were set from Maine to Florida. The whole Atlantic coast was on the lookout for enemy ships. Worried watchfulness was the mood in every newspaper during the following days. On May 11 only the Neue Freie Presse made it clear that the Spanish fleet had been sighted off Puerto Rico, which implied that it was headed for the Antilles and not New York.

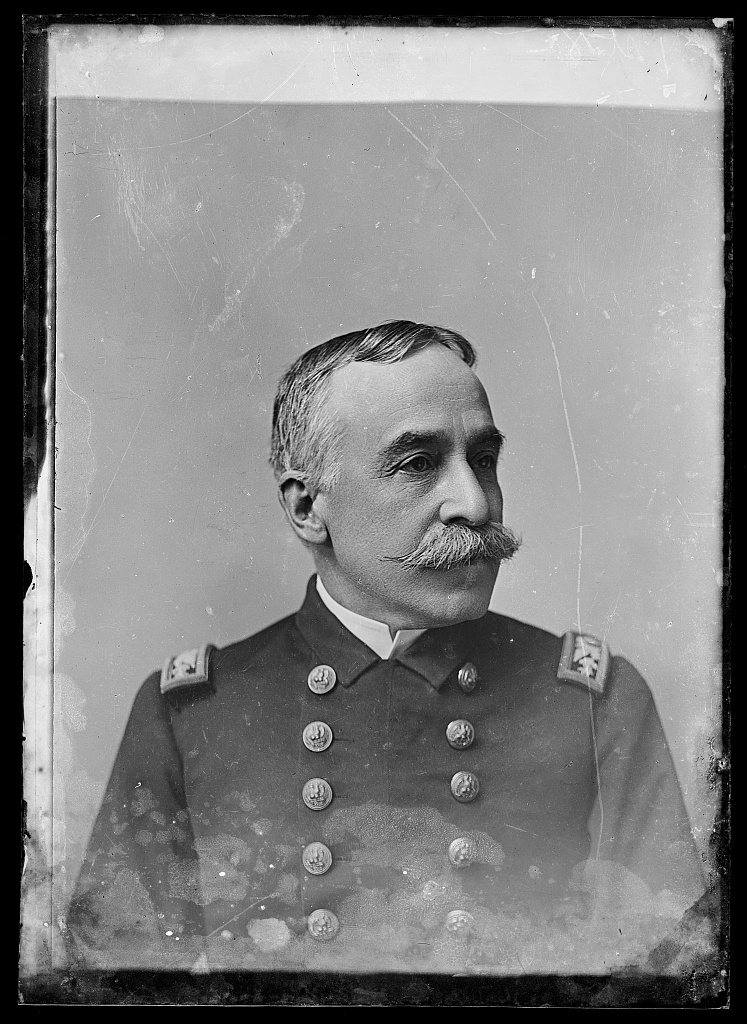

While this international drama developed, a dream-like series of events had unfolded elsewhere. Admiral Dewey, in charge of part of the American fleet, had been in Hong Kong when the war began; he then sailed into the Pacific and had been lost to view. On April 30’s night, Dewey, on his flagship Olympia led his fleet into the harbor of Manila. This action should have led to certain destruction according to the principles of warfare, for the Spanish fleet was entrenched and supplied in a land-locked harbor, and well protected by the guns of fortresses. At 5 o’clock on Sunday morning, May 1, his fleet swept in single file as in a parade in front of the enemy squadron. The Spanish fleet began to fire, but the American ships swept on, not answering the fire in exasperating contempt of the poor marksmanship of the enemy. It looks indeed as if the historical event had already the structure of a dream.

Admiral Dewey, photographed by C. M. Bell, circa 1873-1916, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

“Call off for breakfast!”

The most astounding element was the behavior of Admiral Dewey. According to contemporary press reports, including the Viennese papers that covered the battle in great details, the Admiral stood on his bridge quietly, remarking on the weather and the distant hills, saying that they reminded him of his native Vermont. Half an hour went by while his fleet swept back and forth coming into ever-close range. He finally uttered: “You may fire when you are ready, Gridley”. Sailing in closer ellipses, the American ships all opened fire. At half past seven, after two terrible hours of steady firing, Dewey ordered: “Call off for breakfast!”—a command that would become world-famous. Admiral Dewey interrupted the battle at breakfast time, just when the execution was excellent and there was no resistance on the enemy’s side. Some men cried out “For God’s sake, Captain, to hell with breakfast; give it to them now” while the Spaniards raised a great shout as they thought that the Americans were fleeing.

After breakfast, the firing resumed and lasted several hours. Finally, when the smoke was gone, the Americans could see that all the Spanish ships were sinking or on fire. Captain Cadarso, commander of the Reina Maria Cristina had fallen dead on the bridge, having been replaced by his second in command who was immediately killed. The rear half of the ship had been blown up, and Admiral Montojo, commander of the fleet, would not quit the other half. The marksmanship of the Spaniards was obviously terrible: during the battle not one shot hit any target. Half an hour past noon, in time for lunch, the Spanish fortress hoisted the white flag. Even if the scene of destruction was awful with flaming hulks, shattered fragments of ships, and the water-battery devastated on the Spanish side, this was a “clean war” for the Americans since not one single person on their side was killed.

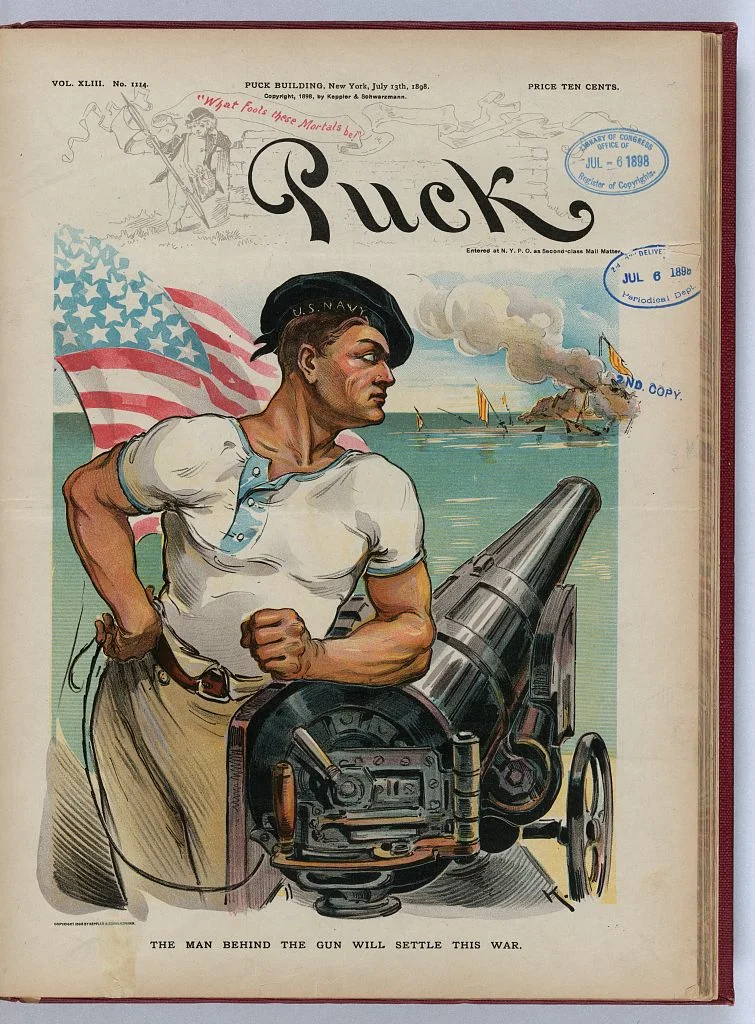

Cover of Puck, July 13, 1898. An American sailor wearing a cap labeled "U.S. Navy", leaning on a ship cannon, with an American flag behind his right shoulder and the ruins of the Spanish fleet in the background. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

During the breakfast truce the Spanish who controlled the city of Manila had sent a message of victory to Madrid. Later on, they sent a second message of defeat concealed in comforting euphemisms. Although victorious, Dewey was prevented by the Spaniards from using the cable. Exasperated, he fished it from the sea and cut it. As a result, the outcome of the battle was learnt much later, when a ship reached Hong Kong. For a whole week, the Americans knew that there had been a battle but were not sure whether Dewey had won or whether the Spanish fleet was heading to New York. Finally, the full story was published in Vienna in the morning of May 10. Only a week after the battle did the public realize that the Spaniards had been defeated and that New York was out of danger.

We see many elements of Freud's dream appearing as repetitions of the battle events. Let us review just a few: Freud talks about “the arrival of enemy warships, because we are in a state of war”, “I hold him [Herr P.] back and ask him in what manner I should let news reach him in case of need. Then he says something else, but at once his head sinks down dead. I may have overstrained him unnecessarily with questions.” It is easy to assume how “overstrained” the international public may have been: submerged in a tense expectation, hearing contradictory accounts, fearing an attack on New York, and worried by the uncertain results of the battle. “I wonder whether I ought to announce the death to the Higher Command, and whether I should take over the control of the castle as next in command.” During the battle, Captain Cadarso, commander of the Reina Maria Cristina was killed and like Herr P., he was replaced by his second in command. Since the cable had been cut after the battle, not only the general public, but even the Higher Command was not properly informed —just who was in control “of the castle” remained unknown between May 1st and May 10th.

“At one ship we are frightened and cry: ‘There comes the warship’.... Now comes a little ship, comically cut off so that it ends in the middle at its broadest; on a deck there are peculiar cup or box-like things. We cry out as of one mouth: ‘That is the breakfast ship.’" As for the “little ship, comically cut off so that it ends in the middle at its broadest,” let us recall that the rear half of Captain Cardarso’s ship had been blown up, and Admiral Montojo, commander of the fleet, would not quit the other half. The appearance of the seemingly nonsensical “breakfast-ship” is self-explanatory after Dewey’s striking dream-like breakfast-truce and his famous command.

This dream of Freud provides us with an excellent example of the function of over-determination: “two interpretations are not mutually contradictory, but both cover the same ground; they are a good instance of the fact that dreams, like all other psychopathological structures, regularly have more than one meaning." Let us note that in this dream the day-residues do not seem to undergo many distortions—they are not mere allusions but reappear almost intact in the dream material. Since, as Freud says, “our dream thoughts are dominated by the same material that has occupied us during the day and we only bother to dream of things which have given us cause for reflection in the daytime" the political implications of the dream are even more relevant.

I will now concentrate on the striking political and historical relevance of this dream taking advantage of the positive character of over-determination. Freud does not see the dream as having only one unique and exhaustive meaning, but he rather sees it as a point of emergence of a series of meanings. Louis Althusser's concept of over-determination (for something to occur there must be several conflicts at work) can help in this case, since the Freudian heritage in Althusser's “symptomatic reading” of Marx's Das Kapital confirms that we need to cross the gap between the social and the individual. Each of Freud’s dream elements is over-determined, even when motivated by very personal and idiosyncratic circumstances, they are still traversed by the effects of a wider context, betraying a connection with the social structure.

Following Lacan’s topological model, one can read the dream as a knot tying different meanings corresponding to various levels. From this perspective, the Freudian idea of over-determination demonstrates that the dream has several causes working together, bringing about a new concept of causality. However, if the manifest content of the dream seems to be motivated by very identifiable daytime ideas, I do not want to stress only one meaning. Thus, I would also like to speculate on the psychic factors instigating this dream in order to trace back its latent content. On that regard, Freud himself offers a lucid interpretation of the dream. Freud alludes to a line of Schiller “Still, auf gerettetem Boot, triebt in den hafen der Greis,” (Safe on his ship, the old man quietly sails into port) allegorizing life and death. He analyzes this dream as expressing fears about his own death. Interestingly, Freud notes that the Governor’s death left him quite indifferent despite the fact that his analysis showed that Herr was a substitute for himself. Freud’s fears concern the future of his family after his premature death. The profound impression awoken by the arrival of the warship led him to recall an event, which occurred a year earlier while he was in a “magically beautiful day at the room on the Riva degli Schiavoni” in Venice. At the sight of a ship, his wife had cried out “gaily as a child: Here comes the English warship.” When those words reappear in the dream, they are cause for deep fright.

The “tense and sinister impression” at the end of the dream is produced by the return of the shipwreck (Shiffbruch, literally “ship-break”)—the cut-off, broken-off ship. Freud analyses the appearance of the “breakfast-ship” by referring to the world English, which is the leftover of his wife's phrase, "Here comes the English" warship that in the dream becomes, "Here comes the warship." We can locate this missing signifier when it reappears in the English word “breakfast.” “Break” relates to ship-break and “fast” becomes “fasting”, then connected to a mourning dress. Freud notes that the breakfast ship was comically cut off and on the deck had peculiar cup or box-like things that had great resemblance with some objects that had attracted his attention when he had seen them in Etruscan museums. They were rectangular trays of black pottery similar to modern-day breakfast-sets. These, were in fact the toilette objects of an Etruscan lady. The idea of black toilette related also to a mourning dress; thus, is making a direct reference to death. Then, Freud attributes the origin of the breakfast-ship to the English word breakfast (literally, breaking fast), linked to both ship-breaking and the black mourning dress.

[B]ut it was only the name of the breakfast ship that was newly constructed by the dream. The thing had existed and reminded me of one of the most enjoyable parts of my last trip. Mistrusting that food would be provided at Aquileia we had brought provisions with us . . . And while the little mail steamer made its way slowly trough the ‘Canale delle Mee’ across the empty lagoon to Grado we, who were the only passengers, ate our breakfast on deck in the highest spirits, and we had rarely tasted a better one. This then, was the ‘breakfast-ship,’ and it was precisely behind this memory of the most cheerful joie de vivre that the dream concealed the gloomiest thoughts of an unknown and uncanny future.

Life and death converging in a pagan wake, in which intense joy and deep fear get all played out in this rich dream. Behind a memory of the happiest joie de vivre, the jouissance de vivre emerges. Freud’s analysis about what lies behind the coining of the “breakfast ship” includes the phrase, “The thing had existed.” It is almost impossible not to hear echoes of both Freud’s and Lacan’s elaborations on das Ding, the “unforgettable thing” that exists beyond our attempts at symbolization. The dream stops when the domain of the Real is encountered.

Freud, still and all, chose not to explore the evident parallel between his inner thoughts and the sociopolitical realm. However, the impact of the historical events that may have brought up “the gloomiest thoughts of an unknown and uncanny future” were clearly there.

Freud family c.1876. Standing left to right: Paula, Anna, Sigmund, Emmanuel, Rosa and Marie Freud and their cousin Simon Nathanson. Seated: Adolfine, Amalia, Alexander and Jacob Freud. Hulton Archive/Getty Images

So the dream will be

In a letter to Fliess written exactly one year after the dream (May 28, 1989), Freud calls the Traumdentung simply der Traum (the dream) and writes: “So the dream will be. That this Austria is supposed to perish in the next two weeks made my decision easier. Why should the dream perish with it?" As William McGrath observes in Freud's Discovery of Psychoanalysis, even though the psychoanalyst's

ironic estimate of Austria’s durability was not borne out, Freud’s sense of impending political disintegration was well founded. The bitter divisions over language, nationality, and class that beset the Habsburg Empire seemed to threaten its existence repeatedly during the closing years of the nineteenth century, when Freud was engaged in what proved to be his most important scientific project.

As Mc Grath notes, Freud’s comment sets the writing of The Interpretation of Dreams against its political background, demonstrating Freud’s awareness of how profoundly influenced his “dream” had been by the political conditions of his day.

If there were political allegiances for Freud, they were mixed. On the one hand, he was worried about his relatives living in New York. Four years earlier, in 1892, the brother of Freud’s wife, Eli Bernays, who was married to Freud’s sister, Anna, emigrated to the United States and in 1898 his relatives were living at 1883 Madison Avenue. However, Freud’s position in the dream fearing the arrival and attack of the breakfast-ship may remind us that he was not very fond of America, that he considered it a “gigantic mistake”, being the “anti-Paradise” and “useful to nothing else but to supply money.” We may assume that Freud regretted the defeat of the Spanish, perhaps in the name of a long-standing Spanish-Austrian allegiance, and sided with the former Empire, now weakened and victimized.

The Viennese Jew Freud may have seen America as “Amerika,” this is, as a mystic writing-pad on which to project his experience of otherness as it may have been the case for the Czech Jew, Franz Kafka. Neither Kafka when he wrote Amerika, nor Freud at the time of the dream, had visited the United States. America—familiar and strange at the same time; fascinating in its otherness.

Patricia Gherovici is a psychoanalyst and the co-founder and director of the Philadelphia Lacan Group. This is a revised excerpt from her book, The Puerto Rican Syndrome (2003).