Alaxchiiaahush was the Siouan name given to a young Crow boy by his grandfather after the elder had a dream-vision that his grandson would live a long and courageous life. Alaxchiiaahush means “many achievements” and the name came to characterize the young warrior’s life in battle, and later, his role as the last great traditional Chief of the Crow Nation (Apsaalooké). The great Chief’s birth name, given to him by his mother, was Chiilaphuchiassaalesh, or Bull Goes into the Wind. White settlers also gave him an English name—Plenty Coups—which would come to be his most well-known moniker thereafter.

Near the end of his life Plenty Coups shared these details, as well as other biographical information, with Frank Bird Linderman, a white man from Montana. Linderman was a respected writer during the early 20th century who had befriended the Crow Chief. Their conversations would culminate with Linderman’s biography of Plenty Coups, originally published in 1930 under the title, American: The Life Story of a Great Indian, and later as Plenty Coups: Chief of the Crows.

Plenty Coup, chief of the Crow. Photograph by Edward S. Curtis, Library of Congress, Curtis Collection

Frank Bird Linderman. Photograph courtesy of the Frank Bird Linderman Memorial Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Maureen and Mike Mansfield Library, The University of Montana-Missoula.

Linderman’s account of the life of Plenty Coups has been given new significance in Jonathan Lear’s 2006 book Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation. Linderman’s text is significant for Lear because it is a biographical account of the Chief who witnessed the end of the traditional Crow way of life and who managed to lead his nation into a future that was inconceivable. Linderman’s biography is also significant because it is an account of a cross-cultural conversation between two disparate figures.

Lear focuses two particular moments of this conversation. The first is Plenty Coups’s insistence on only sharing stories from his life prior to being moved to a reservation:

“I have not told you half of what happened when I was young,” [Plenty Coups] said, when urged to go on. “I can think back and tell you much more of war and horse-stealing. But when the buffalo went away the hearts of my people fell to the ground, and they could not lift them up again. After this nothing happened. There was little singing anywhere. Besides,” he added sorrowfully, “you know that part of my life as well as I do. You saw what happened to us when the buffalo went away.”

Plenty Coups’s utterance, “after this nothing happened,” is the basis for Lear's exploration of the idea of radical hope, which he defines as the courage to continue in the face of cultural devastation—when one loses the very framework for understanding one’s sense of existence.

Lear also takes interest in a dream-vision that Plenty Coups had when he was nine years old:

As a youth, alone in the woods for a few days as part of a tribal ritual of manhood, Plenty Coups dreamt of a storm that would fell all but one of the trees of the forest. On that one, lone surviving tree was a chickadee, a humble member of the Crow people’s aviary pantheon, noted for its capacity to listen and adaptatively change course. When Plenty Coups returned, he told the dream to the tribal elders who interpreted it to mean that the Crow would face some catastrophe (the dream’s devastating storm) and that to survive it they would have to adapt from Crow virtues to Chickadee ones: from war virtues to other, more humble habits like listening, observing, and adapting to new situations, trading one sort of courage (martial) for another. They thought that the old Chickadee, who was no Crow, would have to be repurposed as a new icon of a new kind of courage and take the old Crow’s place.

As one tribal elder put it, “The tribes who have fought the White man have all been beaten, wiped out. By listening as the Chickadee listens, we may escape this and keep our lands.”

A portrait of Chief Plenty Coups and Bull Snake. Photograph courtesy of the Richard Throssell Collection, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming. Original photograph by Throssel Photocraft Company, 6.5x8.5 inch glass plate negative.

Plenty Coups presented his dream to the Crow elders, but only shared Yellow-Bear’s interpretation with Linderman. Yellow-Bear, the wisest elder of the Crow nation at the time, believed Plenty Coups’s dream to be a vision of the future where the buffalo have been eliminated and the white men have taken control. However, Yellow-Bear also saw a positive warning in the dream. He believed that by listening and learning from others as the Chickadee does, the Crow could avoid the fate of other nations. Lear, aware of his position as a non-Indigenous man attempting to interpret the context and significance of Plenty Coups’s dream, provides a responsible analysis of the co-operative and public nature of dream interpretation for the Crow. Nonetheless, just as the elders of the Crow nation did, Lear works to address the larger philosophical and political consequences of the activity of interpretation.

During a public lecture in Sydney, Australia in 2015, Lear described how he felt personally addressed to "re-cognize" and take up the responsibility to rethink the significance of Plenty Coups’s life (at approximately 25:00). Rather than attempting to get to “the truth” of the dream in any authoritative or objective sense, the important task became “re-cognizing” the unique situation that the Crow nation faced and the legitimacy of their approach to facing it. For Lear, this included not only learning more about Crow culture before and after the moment where “nothing happened,” but also learning about this history from the people bound to it.

The primary concern of Radical Hope is a consideration of what it means to have hope and courage in the face of a profound cultural loss, moments when these fundamental concepts themselves lose meaning. The book also opens up questions about what it means to try to recognize the other in the face of hundreds of years of colonization and mis-recognition. During his lecture in Sydney, Lear defines recognition as the feeling of being called to address this cross-cultural dilemma. He emphasizes the idea that one must not only think about the content of an issue, but also the assumptions from which one is approaching the issue.

To rethink recognition is to move beyond understanding recognition as a simple acknowledgement of otherness and a seemingly respectful and distanced coexistence that maintains colonial standards and structures of power. In this model, recognition then becomes a deeper reading of the social text—in this case, Plenty Coups’s dream—and the cross-cultural conversation in which it emerged. Here recognition is not merely a search for familiarity or understanding. Rather it becomes a different way of participating in a cross-cultural conversation: beginning with the admission of a lack of understanding opens an opportunity for engagement through difference. The failure—and indeed, the repeated failure—to understand the other becomes the necessary point from which one begins to engage in the project of cross-cultural exchange.

Repeated failures exist throughout the story of Plenty Coups’s life, but his unrelenting hope and commitment to collaborative interpretation exceeded them. For example, in moments of uncertainty and doubt, Plenty Coups did not turn inwards. Instead, his dependency on others was, as Bonnie Honig says, “not disavowed but owned.” In accordance with Crow custom, Plenty Coups shared his dream-vision with the elders, transforming it into a what Honig calls a “public thing.” That is, the interpretation of the dream and the hope flowing from it became a collective interest and a shared responsibility. Later, when Plenty Coups shared his story with Linderman, he did so knowing that the two lacked a mutual framework for understanding each other. The reality of this lack did not stop Plenty Coups from making the story of his dream and life public once again. This reality made both men take responsibility for the care of the story and for the dependency between them. Furthermore, this interaction made listening a core element of cross-cultural negotiation.

For Plenty Coups, the dream-vision revealed a way for the Crow people to begin again after cultural genocide: follow the listening way of the chickadee. The Chickadee-person is described as “least in strength but strongest of mind amongst his kind. He is willing to work for wisdom. The Chickadee-person is a good listener.” The tribe’s use of Plenty Coups's dream—its commitment to mobilizing it collectively—gave the Crow nation guidance and purpose during a time when the traditional Crow way of life was being destroyed. This dream-vision helped Plenty Coups symbolically represent this devastation. Indeed, through the insight provided by the dream, he could both proclaim the end of one way of life and begin to construct a future, to formulate a new way of living. Plenty Coups’ dream-vision helped the Crow become, once again, the primary narrators of their own existence. And it helped lead them to negotiate the role that white settlers would play in this project.

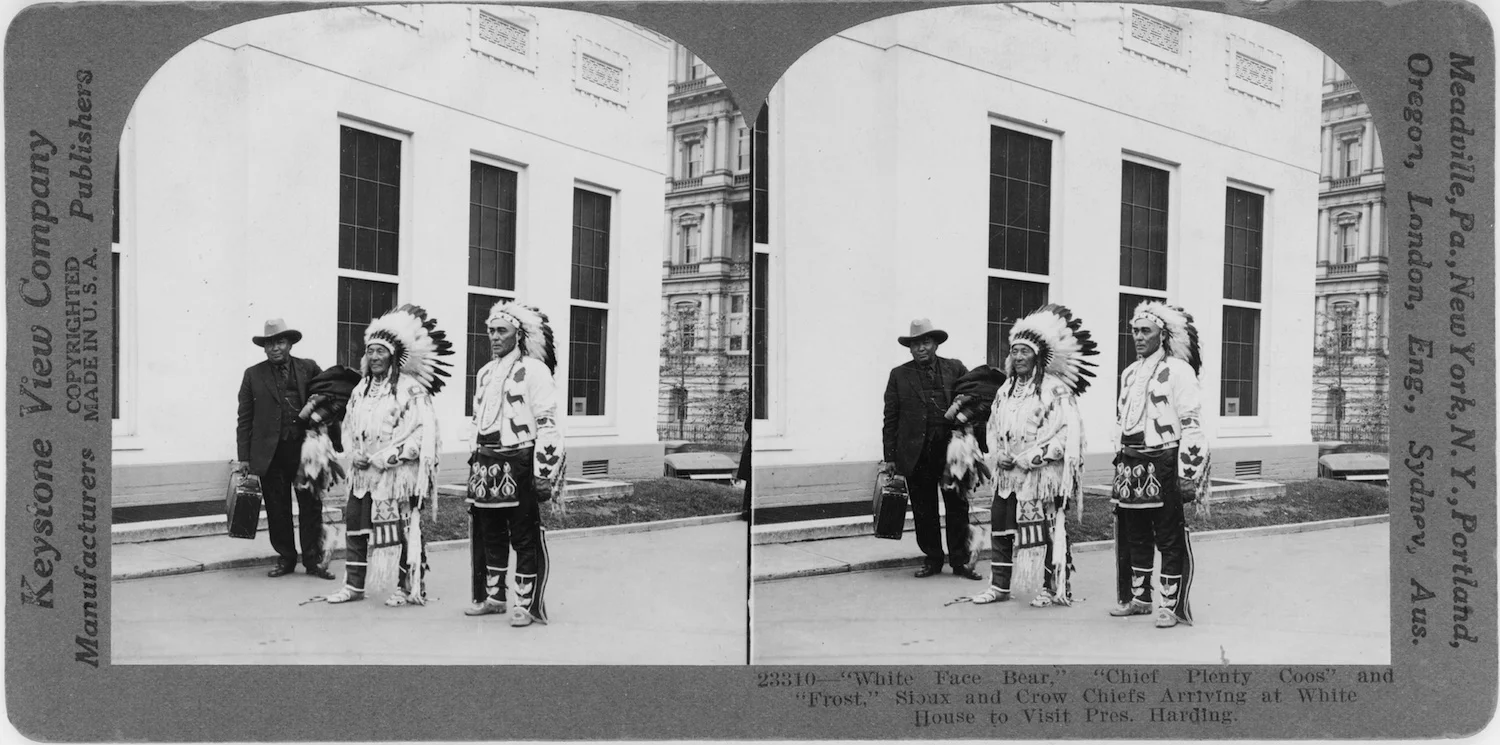

"White Face Bear," "Chief Plenty Coups" and "Frost," arriving at White House to visit President William G. Harding. Keystone View Company, stereo card, c. 1921. Library of Congress

The stakes of cross-cultural negotiation is an ongoing issue. Indigenous scholars, artists, and activists across Turtle Island are calling for Indigenous communities to move towards modes of cultural and political self-determination. Indigenous artists, such as A Tribe Called Red, who are giving life to the dreams and poetry of writer and activist John Trudell, are opening new spaces within the public consciousness for these processes of self-determination. These are also opportunities for members of settler cultures to address their responsibility to “re-cognize”—to actively engage in cross-cultural projects of recognition.

It is not the responsibility of Indigenous peoples to decolonize settler cultures. However, it is not possible for settler cultures to decolonize themselves by remaining within their own colonial framework of understanding. The restructuring of frameworks of knowledge is the responsibility of those bound to them, but it is the cross-cultural exchange that fuels this process. Interrogating the processes of recognition and re-thinking the terms of cross-cultural exchange are essential practices for reconciliation and decolonization. And as Plenty Coups’ story suggests, attending to dream-visions is one way to undertake this project.

—Ryan Shuvera is a PhD student at the Centre for the Study of Theory & Criticism at Western University where he studies sonic forms of resistance to settler colonialism.

"The Chickadee Dream" © February 2017